|

|

Dr.

Larry Farwell's

Brain

Fingerprinting Test

Helps to

Bring a Serial Killer to

Justice

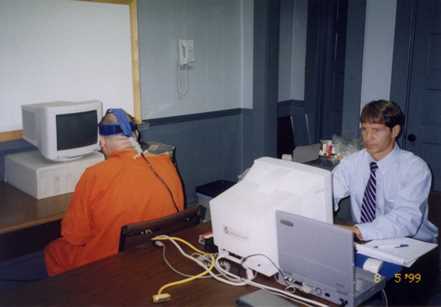

Dr. Farwell conducts

a Brain Fingerprinting test on

serial killer J. B. Grinder

For

15 years,

James B.

Grinder was

the primary

suspect in the

brutal murder

case of Julie

Helton, but

there had

never been

enough

evidence to

bring him to

trial. Miss

Helton was

reported

missing in

Macon, MO in

January 1984.

Three days

later her body

was found near

the railroad

tracks in

Macon. She had

been raped,

brutally

beaten and

stabbed.

During the 15

years after

the murder,

Grinder had

given several

different,

contradictory

accounts of

the crime.

Some accounts

involved his

participation

and some did

not. Some

involved

participation

by several

other

individuals.

Grinder's

accounts

contradicted

both the

physical

evidence and

the statements

of an alleged

witness.

After spending

over 10,000

man-hours

investigating

the case,

Macon County

Sheriff Robert

Dawson asked

Dr. Lawrence

Farwell to use

Brain

Fingerprinting

testing to

determine

scientifically

whether or not

Grinder was

the

perpetrator of

the crime.

Grinder,

already

serving time

in jail on an

unrelated

case, agreed

to participate

in the Brain

Fingerprinting

test. Sheriff

Dawson, Chief

Deputy Charles

Muldoon, and

Randy King of

the Missouri

Highway Patrol

provided Dr.

Farwell with

the specific

background

information on

the case for

use in

developing the

test. Dr. Drew

Richardson,

then an FBI

Supervisory

Special Agent,

worked with

Dr. Farwell to

structure the

Brain

Fingerprnting

test.

During

the Brain

Fingerprinting

test, which

Dr. Farwell

administered

in August

1999, Grinder

viewed short

phrases

flashed on a

computer

screen, some

of which were

probe stimuli

containing

specific

details of the

crime that

would be

noteworthy

only to the

perpetrator.

These included

the murder

weapon, the

specific

method of

killing the

victim,

specific

injuries

inflicted on

the victim by

the

perpetrators

before she was

killed, what

the

perpetrators

used to bind

the victim’s

hands, the

place where

the body was

left, items

that the

perpetrators

left near the

crime scene

and items that

were taken

from the

victim during

the crime.

Computer

analysis of

the Brain

Fingerprinting

test found,

with a

statistical

confidence

level of

99.9%, that

the specific

details of the

crime were

recorded in

Grinder’s

brain as

“information

present”,

which means

that record

stored in

Grinder’s

brain matched

the details of

Julie Helton

‘s murder.

Following the

test results,

Grinder faced

an almost

certain

conviction and

probable death

sentence.

Grinder pled

guilty to the

rape and

murder of

Julie Helton

in exchange

for a life

sentence

without

parole.

He is

currently

serving that

sentence. In

addition,

Grinder

confessed to

the

murders of

three other

young women.

Testing

Procedure

Dr.

Farwell's

Brain

Fingerprintng

test followed

the Brain

Fingerprinting

Scientific

Standards,

as specified

in Dr.

Farwell's

peer-reviewed

publications

and ruled

admisible in

court. Grinder

wore a

headband

equipped with

sensors that

measured his

brainwave

responses to

words and

phrases, some of

which contained

relevant

information to the

crime

that

was known only to

the perpetrator

and

investigators.

The Brain

Fingerprinting system

mathematically analyzes the

brain-wave responses and makes a

determination of “information

present’ or “information

absent”. “Information present”

means that the probe responses,

like the target responses,

contain a P300-MERMER indicating

that the crime-relevant

information is stored in the

brain. “Information absent”

means that the details of the

crime are not stored in the

brain. The Brain Fingerprinting

system also computes a

statistical confidence for the

determination of “information

present” or “information

absent.”

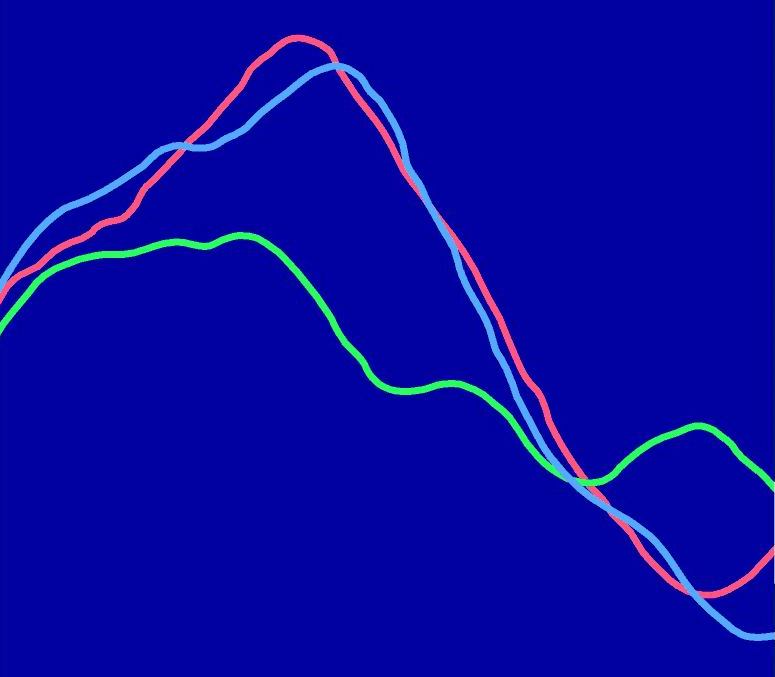

Test Results

Grinder’s

brainwave responses to the words and

phrases

containing details of the rape

and murder of Julie Helton

clearly contained a P300-MERMER,

indicating “information present”

which means that the details of

this crime were stored in his

brain. (As expected, the target

responses also elicited a

P300-MERMER, and the irrelevant

responses did not elicit a

P300-MERMER.)

The Brain

Fingerprinting test result for

J.B. Grinder was “information

present,” with a statistical

confidence of 99.9%. From this

we can conclude with a high

degree of confidence that, even

though fifteen years had passed

since the event, significant

details of Julie Helton’s rape

and murder are stored in J.B.

Grinder’s brain.

One

week after Dr.

Farwell's Brain

Fingerprinting test

on him,

Grinder,

faced with

certain

conviction and

probable death

sentence, pled

guilty to the

rape and

murder of

Julie Helton

in

a plea bargain

in exchange

for a sentence

of life in

prison without

parole.

He is now

serving that

sentence.

He also

confessed to

the murders of

three

other young

women.

Dr. Larry Farwell's Brain

Fingerprinting Test

on Serial

Killer JB Grinder

Grinder's

Brainwave

Responses

Letter

from Sheriff Robert Dawson on Dr.

Farwell's Brain Fingerprinting test

of JB Grinder

The Terry Harrington Case

Farwell Brain

Fingerprinting Helps to Free an

Innocent Man

after

24

Years

in Prison

Ruled Admissible in

Court

Dr.

Larry Farwell Conducts

a

Brain Fingerprinting

Test on Terry

Harrington

Terry

Harrington spent over

half of his life in

prison for murder.

Twenty-three

years after his

conviction, Dr.

Lawrence Farwell used

Brain Fingerprinting

testing to show with a

99.9% statistical

confidence level that

the record stored in

Harrington's brain

does not match the

crime scene and does

match his alibi. The

testing showed that

significant details of

the crime are not

stored in his brain.

The judge ruled that

Brain Fingerprinting

is admissible as

scientific evidence in

court. On February 26,

2003 the Iowa Supreme

Court reversed his

murder conviction and

ordered a new trial.

In

October 2003, the

State of Iowa elected

not to re-try Mr.

Harrington and

released him from

prison.

In 1977,

Harrington, who was 17

at the time, was arr

ested for

the murder of John

Schweer, a retired police

captain who had been

working as a security

guard. Court records

contain contradictory

accounts of the events of

the evening of the crime.

In the trial, Harrington

said that he had been with

friends at a concert the

evening of the murder.

Several witnesses

corroborated this alibi.

The primary prosecution

witness, 16-year old Kevin

Hughes, told a different

story. He gave a detailed

account of Harrington's

alleged perpetration of

the crime. A year later

Harrington was found

guilty and sentenced to

life without parole, based

almost entirely on Hughes'

testimony.

Now Brain

Fingerprinting

technology has made it

possible to examine

scientifically which

sequence of events

actually took place, by

determining which one is

stored in Harrington's

brain. Brain

Fingerprinting testing

determines objectively

what information is

stored in a person's

brain by measuring

brain-wave responses to

relevant words or

pictures flashed on a

computer screen. When

the brain recognizes

significant information

— such as the details of

a crime stored in the

brain of the perpetrator

— the brain responds

with a MERMER (memory

and encoding related

multifaceted

electroencephalographic

response). When the

information is not

stored in the brain, no

MERMER occurs.

In 1997,

nineteen years after his

conviction, Harrington

petitioned the Iowa

District court for

post-conviction relief

alleging several grounds

for granting him a new

trial, and in March

2000, he amended his

petition to include the

results of the Brain

Fingerprinting

testing.

In the

Brain Fingerprinting

tests, Harrington's

brain did not emit a

MERMER in response to

critical details of the

murder, details he would

have known if he had

committed the crime,

indicating that this

information was not

stored in his brain. In

a second Brain

Fingerprinting test, one

that included details

about Harrington’s

alibi, Harrington's

brain did respond with a

MERMER, indicating that

his brain recognized

these events. The

details used in the

second test were facts

about the alibi that Dr.

Farwell obtained from

official court records

and alibi witnesses.

"It is

clear that Harrington's

brain does not contain

critical details about

the crime," said Dr.

Farwell. "His brain

does, however, contain

critical details about

the events that actually

took place that night,

according to alibi

witnesses who testified

that Harrington was in

another city with

friends at the time of

the crime. We can

conclude scientifically

that the record of the

night of the crime

stored in Harrington's

brain does not match the

crime scene, and does

match the alibi."

When Dr.

Farwell confronted him

with the Brain

Fingerprinting test

results exonerating

Harrington, Kevin

Hughes, the key

prosecution witness,

recanted his testimony

and admitted that he had

lied in the original

trial, falsely accusing

Harrington to avoid

being prosecuted for the

murder himself.

In

November 2000, the Iowa

District Court for

Pottawattamie County

held a hearing on Terry

Harrington’s petition

for post-conviction

relief from his sentence

for murder. This hearing

included an eight-hour

session on the

admissibility of the

Brain Fingerprinting

test report. In March

2001, District Judge

Timothy O’Grady ruled

that Brain

Fingerprinting testing

met the legal standards

for admissibility in

court as scientific

evidence.

The

judge also ruled,

however, that the

results of the Brain

Fingerprinting test,

along with other newly

discovered evidence in

the case, would probably

not have resulted in the

jury arriving at a

different verdict than

at the original trial,

and therefore he denied

the petition for a new

trial.

In August

2001, an appeal of the

District Court’s

decision denying

Harrington a new trial

was filed with the Iowa

Supreme Court. Dr.

Farwell and his

attorney, Tom Makeig,

filed an amicus (friend

of the court) brief in

support of Harrington’s

appeal, based on the

Brain Fingerprinting

testing evidence. The

Iowa Supreme Court

reversed Harrington’s

murder conviction and

ordered a new trial.

In

light of the new

evidence, and considering

that the only

alleged

witness to the

crime had

recanted and

admitted he

lied when Dr.

Farwell confronted

him with the exculpatory

Brain

Fingerprinting

evidence, the

State

of Iowa elected

not to try

Harrington

again.

Harrington and another man

falsely

convicted of the same crime

sued the county, the prosecutors, and the police for framing

him. The

United States Supreme Court agreed to hear the case against the county. Before the case reached

the Supreme Court, however, Pottawattamie County, Iowa settled out of court, paying Harrington and his co-defendant

$12 million.

Farwell

Brain Fingerprinting

Ruled

Admissible

as Scientific Evidence in Court

In

a hearing in

the Terry

Harrington

murder case,

Pottawattamie

County, Iowa

District Court

Judge Tim

O'Grady ruled

that Brain

Fingerprinting

testing is

admissible in

court. Dr.

Farwell

conducted a

Brain

Fingerprinting

test on Terry

Harrington,

who was

serving a life

sentence in

Iowa for a

1977 murder.

The test

showed that

the record

stored in

Harrington's

brain did not

match the

crime scene

and did match

the alibi.

Harrington

filed a

petition for a

new trial

based on newly

discovered

evidence,

including the

Brain

Fingerprinting

test. The Iowa

Supreme Court

reversed his

murder

conviction and

ordered a new

trial. The

Iowa Supreme

Court left

undisturbed

the law of the

case

establishing

the

admissibility

of the Brain

Fingerprinting

evidence.

The Harrington

case is

described

above.

In a Brain

Fingerprinting

test, words,

pictures or

sounds

describing

salient

features of a

crime are

presented by a

computer,

along with

other,

irrelevant

information,

that would be

equally

plausible for

an innocent

subject. Items

are chosen

that would be

known only to

the

perpetrator

and to

investigators,

but not to the

public or to

an innocent

suspect. The

subject is

told which

features he

will see

(e.g., the

murder

weapon), but

is not told

which item is

correct (e. g,

gun, knife, or

baseball bat).

When a subject

recognizes

something as

significant in

the current

context, the

brain emits a

specific brain

response. If

the record of

the crime is

stored in the

subject's

brain, this

response

appears when

the subject

recognizes the

correct,

relevant

items. If not,

then the

response is

absent. A

computerized

mathematical

analysis of

the data

determines

whether or not

the subject

has knowledge

of the salient

details of the

crime.

Just as a

personal

computer emits

a

characteristic

sound whenever

its central

processing

unit is

transferring

information to

or from or the

hard drive,

the human

brain emits a

characteristic

electrical

brain wave

response,

known as a

P300 and a

P300-P300-MERMER

(memory and

encoding

related

multifaceted

electroencephalographic

response),

whenever the

subject

responds to a

known

stimulus. The

P300

electrical

brain wave

response, one

aspect of the

larger

P300-MERMER

response

discovered and

patented by

Dr. Farwell,

is widely

known and

accepted in

the scientific

community.

There have

been hundreds

of studies

conducted and

articles

published on

it over the

past

thirty-plus

years. The

P300-MERMER, a

longer and

more complex

response than

the P300,

comprises a

P300 response,

which is

electrical

events

occurring 300

to 800

milliseconds

after the

stimulus, and

additional

data occurring

more than 800

milliseconds

after the

stimulus.

While a P300

shows only a

peak

electrical

response, a

P300-MERMER

has both a

peak and a

valley.

In order to be

admissible

under the

prevailing

Daubert

standard, the

science

utilized in a

technology is

evaluated

based on the

following four

criteria: (The

Iowa courts

are not bound

by the Daubert

criteria used

in the federal

courts, but

they do use

them when

determining

the

admissibility

of novel

scientific

evidence.)

1. Has the

science been

tested?

2. Has the

science been

peer reviewed

and published?

3. Is the

science

accurate and

are there

standards for

its

application?

4. Is the

science well

accepted in

the scientific

community?

The judge

ruled that

Brain

Fingerprinting

testing met

all four of

the legal

requirements

for being

admitted as

valid

scientific

evidence. The

ruling stated:

"The test is

based on a

'P300

effect.'… "The

P300 effect

has been

studied by

psycho-physiologists…The

P300 effect

has been

recognized for

nearly twenty

years. The

P300 effect

has been

subject to

testing and

peer review in

the scientific

community. The

consensus in

the community

of

psycho-physiologists

is that the

P300 effect is

valid…."

The judge also

ruled that

"The evidence

resulting from

Harrington's

'brain

fingerprinting'

test… is newly

discovered"

and "material

to the issues

in the case,"

and thus meets

the standard

for being

considered in

a petition for

a new trial.

The Brain

Fingerprinting

test on

Harrington

showed that

the record

stored in his

brain did not

match the

crime, and did

match his

alibi. This is

similar a

finding that

Harrington's

fingerprints

or DNA did not

match the

fingerprints

or DNA at the

crime scene,

and did match

those at the

scene of the

alibi.

Dr. Farwell

conducted two

different

analyses of

the data on

Harrington.

Both yielded

the same

conclusion. He

performed the

test and the

analyses in

strict

accordance

with the P300

science that

has been

extensively

researched and

is well

accepted in

the scientific

community. In

another

analysis, Dr.

Farwell used

more

state-of-the-art

techniques,

including the

P300-MERMER,

which, though

arguably more

accurate, do

not yet have

the same level

of acceptance

as the P300.

After

obtaining the

results of the

Brain

Fingerprinting

test, Dr.

Farwell

located the

only alleged

witness to the

crime, Kevin

Hughes. When

Dr. Farwell

confronted him

with the Brain

Fingerprinting

test results

exonerating

Harrington,

Hughes

admitted that

he had lied at

Harrington's

trial. He

stated under

oath that he

had made up

the story

about

Harrington

committing the

crime to avoid

being

prosecuted

himself.

Harrington’s

attorney used

Hughes'

recantation

along with

Brain

Fingerprinting

test findings

as evidence in

his

post-conviction

petition for a

new trial.

The Harrington

case was about

as difficult a

case as could

be envisioned

for the Brain

Fingerprinting

system. The

day after the

crime, the

perpetrator

knows all

about the

crime and an

innocent

suspect knows

nothing.

Scientists

could have

readily

constructed a

Brain

Fingerprinting

test to

distinguish

between the

two, if the

technique had

been invented

at the time.

Later, in his

trial,

Harrington was

exposed to

extensive

information

about the

crime. This

made it

difficult

after the

trial to

produce

salient

features of

the crime that

he would know

only if he had

committed the

crime.

Twenty-three

years after

the crime was

committed,

through

examination of

court

documents,

police

reports,

witness

interviews,

crime-scene

photos and an

investigation

of crime scene

itself, Dr.

Farwell was

able to

structure a

Brain

Fingerprinting

test that

tested

Harrington's

brain for

evidence of

salient

features of

the crime,

features that

he claimed not

to know

because he was

not there. The

test showed

that

Harrington's

brain in fact

did not

contain a

record of

these salient

features of

the crime. A

second test

conducted by

Dr. Farwell

showed that

Harrington's

brain did

contain the

details of his

alibi.

As with other

scientific

evidence,

Brain

Fingerprinting

testing does

not prove

guilt or

innocence per

se. It

provides

information

about what is

stored in the

suspect's

brain. A judge

or jury can

utilize this

information in

making the

legal

determination

of guilt or

innocence. The

weight of the

Brain

Fingerprinting

test evidence

will be

evaluated

along with

other evidence

by a higher

court in their

consideration

of

Harrington's

appeal. If a

higher court

finds that

this and other

evidence

probably would

have changed

the result of

the original

trial if it

had been known

at the time,

then

Harrington

will be

granted a new

trial.

"I believe the

court’s

admission of

Brain

Fingerprinting

test results

into evidence

is a landmark

in forensic

science," said

Dr. Farwell.

"Innocent

persons have a

new technology

to aid in

their

exoneration,

and law

enforcement

has a new

weapon with

which to

convict

perpetrators.

In the future

we can use

this

technology to

find out the

truth early in

a case. This

will save

innocent

suspects from

a traumatic

investigation

and trial, and

potentially

from false

conviction and

punishment. By

allowing law

enforcement to

focus on the

actual

perpetrators,

it will also

save time and

money in law

enforcement.”

"I believe

that in time

we will be

able to

virtually

eliminate

false

convictions

through Brain

Fingerprinting

tests and

other

scientific

technologies

such as DNA

and

fingerprints.

This new

scientific

technology

will also

allow us to

significantly

increase the

number of

actual

criminals

brought to

justice."

Hundreds of

scientific

studies on

this

technology

from dozens of

laboratories

have been

published in

the

peer-reviewed

scientific

literature.

Dr. Farwell

has applied

the technique

not only in

rigorous

laboratory

studies but

also in over

100 real-life

cases. Dr.

Farwell and

then FBI

scientist Dr.

Drew

Richardson

used the Brain

Fingerprinting

system to

detect with

100% accuracy

which people

in a group

were FBI

agents and

which were not

by measuring

brain

responses to

items only an

FBI agent

would

recognize.

Brain

Fingerprinting

testing was

also 100%

accurate in

three studies

Dr. Farwell

conducted for

a US

intelligence

agency and for

the US Navy.

The Brain

Fingerprinting

system tests

for knowledge

of salient

features of a

crime stored

in the brain.

Scientists

know that we

don't remember

everything,

but we do

remember

significant

features of

major events —

like

committing a

serious crime.

By

scientifically

determining

what is stored

in a suspect's

brain, Brain

Fingerprinting

testing

provides

evidence that

can be used by

judges and

juries in

making a

determination

as to whether

the suspect

committed the

crime or not.

Links

Legal

article by Farwell

and Makeig in

Open Court

on Brain

Fingerprinting

in the

Harrington

case

Legal

article in Yale

Journal of Law

and Technology

on

Admissibility

of Brain

Fingerprinting

in US Courts

News:

Farwell Brain

Fingerprinting

ruled

admissible in

the Harrington

case

Fairfield

Ledger News

Report: Farwell

Brain

Fingerprinting

Catches a

Serial Killer

News Report: Farwell's

Brain

Fingerprinting

Catches a

Serial Killer

in Missouri

Peer-reviewed

scientific

paper in Cognitive

Neurodynamics

reporting

on Grinder

case and

relevant

research.

Copyright© 2013 - 2017

Dr. Larry Farwell.

Other trademarks and copyrights

retained by their respective

owners.

|